Gary Stevenson, Ray Dalio

Trading Game (Gary Stevenson) and How Countries Go Broke: The Big Cycle (Ray Dalio)

Trading Game (Gary Stevenson) and How Countries Go Broke: The Big Cycle (Ray Dalio)

Couldn't load pickup availability

Nick's review

Gary Stevenson’s The Trading Game and Ray Dalio’s How Countries Go Broke: The Big Cycle aren’t just economic texts — they’re dispatches from the fault lines of our time. Stevenson writes from the trading floor, Dalio from the ridge. One offers the immediacy of lived experience; the other, the cool detachment of historical pattern.

Stevenson’s memoir is a Molotov cocktail disguised as a coming-of-age story. His prose — razor-edged and laced with East London cadence — sparkles with wit even as it slices through the machinery of modern finance. A working-class prodigy from Ilford, he catapults into the glass towers of Citibank and finds himself among the gods of finance — men of excess, ego, and adrenaline. His colleagues form a rich tapestry of fantastical characters, offering readers a rare, exhilarating glimpse into the high-octane excesses of London’s trading world.

Stevenson becomes one of Citi’s most profitable traders at the time — not by betting on recovery, but by betting against the economy. His high point is a single tradingstrategy: elegant, ruthless, and brilliantly cynical. Wealth inequality suppresses demand, central banks are trapped, interest rates stay low, and asset prices soar. His colleagues missed the trade. His deferred bonus — when grossed up — suggests he may have generated over $100 million in profit for Citi on that single trading strategy, claiming to be one of the firm’s top performers. The claim triggered a takedown in the Financial Times of London and a rugby-style pile-on from ex-Oxfordian colleagues — a reminder that in finance, envy still compounds faster than interest.

Yet the book’s power lies in its final reckoning. Stevenson doesn’t just expose the system. He exposes himself. The memoir becomes a confession — of complicity, of cognitive dissonance, of a man profiting from a machine he came to despise. It’s not just about money. It’s about meaning — or the search for it.

Dalio’s book, by contrast, unfolds along the contours of history — a meditation on the rhythms of collapse and the quiet inevitability of repetition. He charts the Big Debt Cycles that span centuries, tracing the rise and fall of empires, the slow drift from prosperity to decay. His thesis is clear: democracies, when weakened by inequality and institutional failure in the final phase of the Cycle, begin to unravel. They lose sight of justice and virtue. They become decadent. And when compromise collapses, populist factions — from the hard right and hard left — begin to fight for control.

Dalio’s tone is clinical, but the implications are electric. He doesn’t just describe the slide into autocracy — he treats it as structurally inevitable. Democracies, he argues, are ill-equipped to resolve the crises that emerge at the tail end of these cycles. Into the vacuum steps the demagogue: charismatic, often well-intentioned, but increasingly unaccountable, “The more extreme and uncontrolled these populist leaders are,” Dalio writes, “the more dictatorial and corrupt they are likely to become.”

He traces this arc through history — Caesar, Napoleon, Mussolini, Hitler, Franco, Erdoğan — and warns that the pattern is repeating. He singles out Donald Trump as a uniquely unpredictable figure, writing: “President Trump seems to be more inclined to do previously unimaginable things than any president in the last 80 years — and perhaps any president ever.” It’s not a coup. It’s a slide — slow, structural, and psychologically primed. And Dalio suggests it’s a slide that democracies, under stress, rarely resist.

Dalio’s concern is not just economic. It’s psychological. “The chances of cooperation for mutual benefit are not good,” he writes. The factions no longer see each other as opponents within a shared system — they see each other as existential threats. His warning is stark: “We know from history that extreme factionalism kills.”

Dalio still believes in a landing — the “beautiful deleveraging” — if policy can balance austerity, restructuring, wealth transfers and controlled money printing. But the window is narrowing.

Stevenson doesn’t believe in soft landings. He believes the plane is already in freefall — and the cockpit is empty. His view is that inequality suppresses demand. Central banks are trapped. Interest rates are not a tool — they’re a mirror. Rates are no longer a lever. They reflect inequality, not control it. In Stevenson’s world, the “beautiful deleveraging” is a fantasy. The system can’t be fixed with the tools that broke it.

Both men see the gathering storm — Stevenson from the trading floor, Dalio from the ridge — and both books hum with urgency, insight, and a kind of defiant clarity. Both are a warning – perhaps two sides of the same coin — and both are highly recommended.

Figure 1 US Net Wealth Shares. Source: Ray Dalio, Principles For Navigating Big Debt Crises, p.31.

PUBLISHER REVIEWS

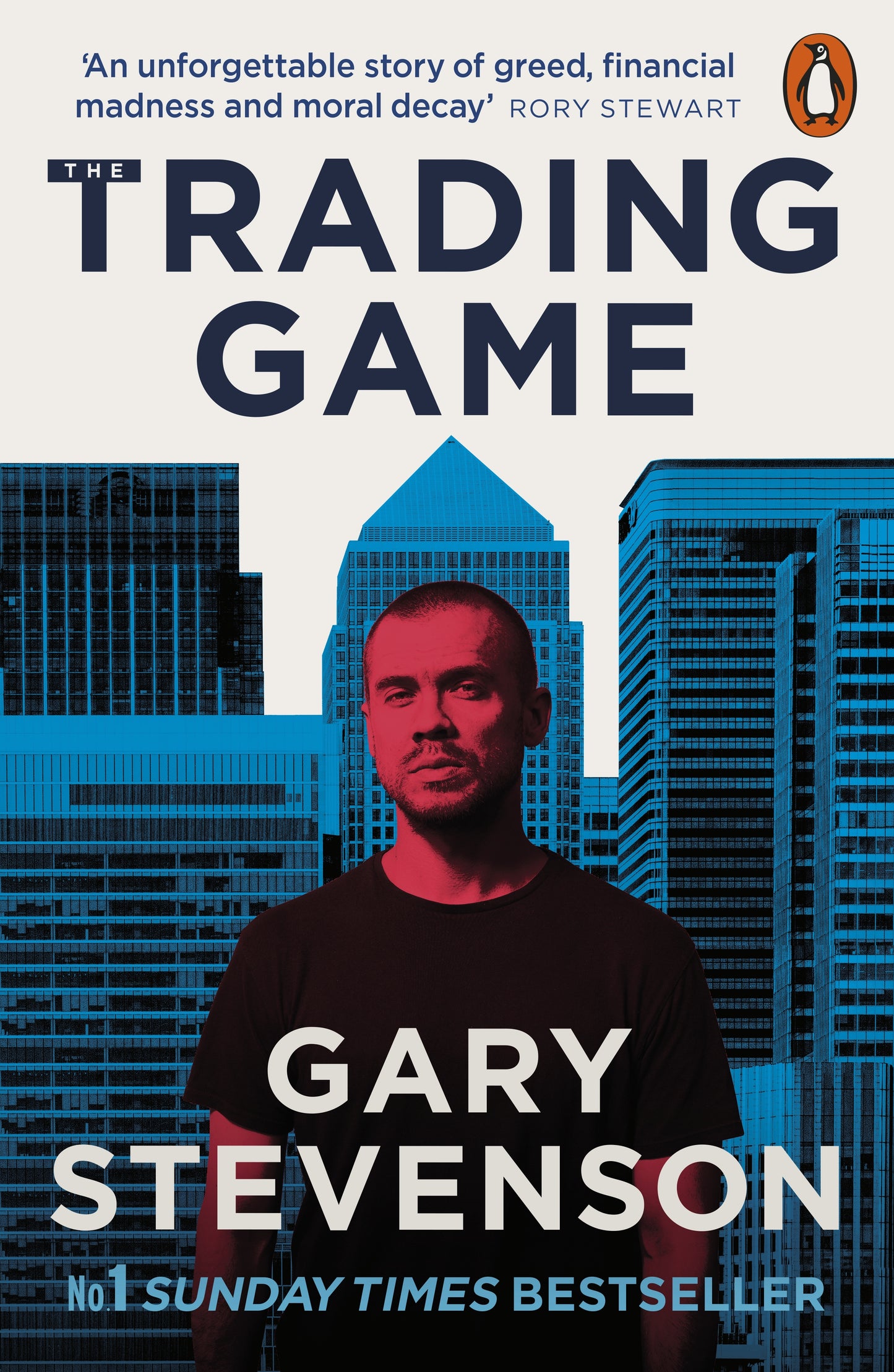

Trading Game by Gary Stevenson

The high-wire true story of the millionaire trader, who won the finance game and then blew it wide open

'If you were gonna rob a bank, and you saw the vault door there, left open, what would you do? Would you wait around?'

Ever since he was a kid, kicking broken footballs on the streets of East London in the shadow of Canary Wharf's skyscrapers, Gary wanted something better. Something a whole lot bigger. Then he won a competition run by a bank- 'The Trading Game'. The prize- a golden ticket to a new life, as the youngest trader in the whole city. A place where you could make more money than you'd ever imagined. Where your colleagues are dysfunctional maths geniuses, overfed public schoolboys and borderline psychopaths, yet they start to feel like family. Where soon you're the bank's most profitable trader, dealing in nearly a trillion dollars. A day. Where you dream of numbers in your sleep - and then stop sleeping at all. But what happens when winning starts to feel like losing? When the easiest way to make money is to bet on millions becoming poorer and poorer - and, as the economy starts slipping off a precipice, your own sanity starts slipping with it? You want to stop, but you can't. Because nobody ever leaves. Would you stick, or quit? Even if it meant risking everything?

This is an outrageous, unvarnished, white-knuckle journey to the dark heart of an intoxicating world - from someone who survived the game.

How Countries Go Broke by Ray Dalio

'Advance copies of Ray Dalio’s new book about how countries go broke have become a hot read in Washington' New York Times

An urgent warning about the global economy from Ray Dalio, the #1 New York Times bestselling author of Principles.

Do big government debts threaten our collective well-being? Are there limits to debt growth? Can a big, important reserve currency country like the United States really go broke – and what would that look like?

For decades, politicians, policymakers and investors have debated these questions, but the answers have eluded them. In this groundbreaking book, Ray Dalio, one of the greatest investors of our time who anticipated the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2010–12 European debt crisis, shares for the first time his detailed explanation of what he calls the 'Big Debt Cycle'. Understanding this cycle is critical for helping policymakers, investors and the general public grasp where we are and where we are headed with the debt issue. Dalio's model points toward surprisingly straightforward solutions for dealing with the debt problems that the US, Europe, Japan and China face today.

How Countries Go Broke also shows how these debt problems are related to the other forces – political within countries, geopolitical between countries, natural (droughts, floods and pandemics) and technological (most importantly, AI) – that together are causing what Dalio calls the 'Overall Big Cycle' changes in the world order. By reading this book, you will improve your understanding of what's happening now and what to do about it.

'This book is a gift to humanity . . . Ray provides a solution to what is the biggest and most certain threat to our prosperity' Henry M. Paulson Jr.

'An invaluable resource for policymakers, investors, and citizens' Lawrence H. Summers

Share