Marika Sosnowski

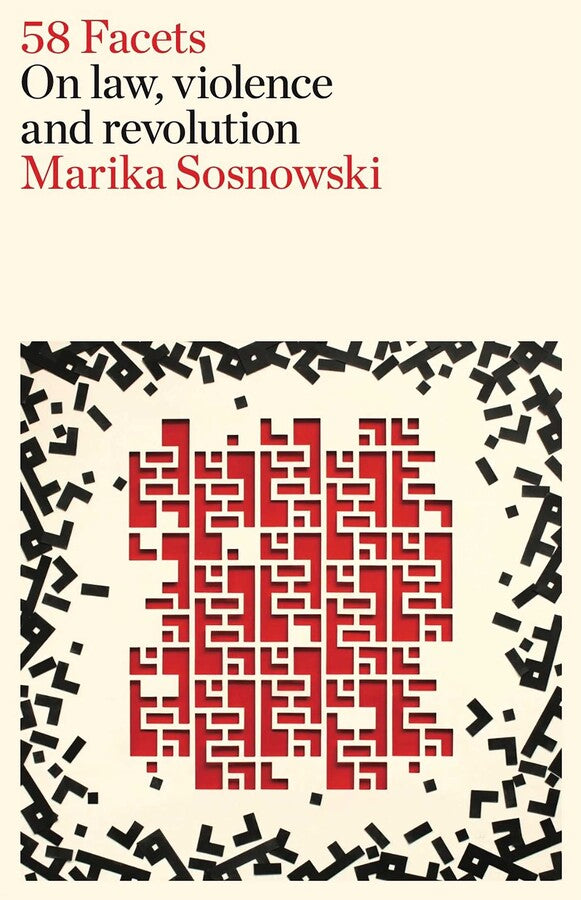

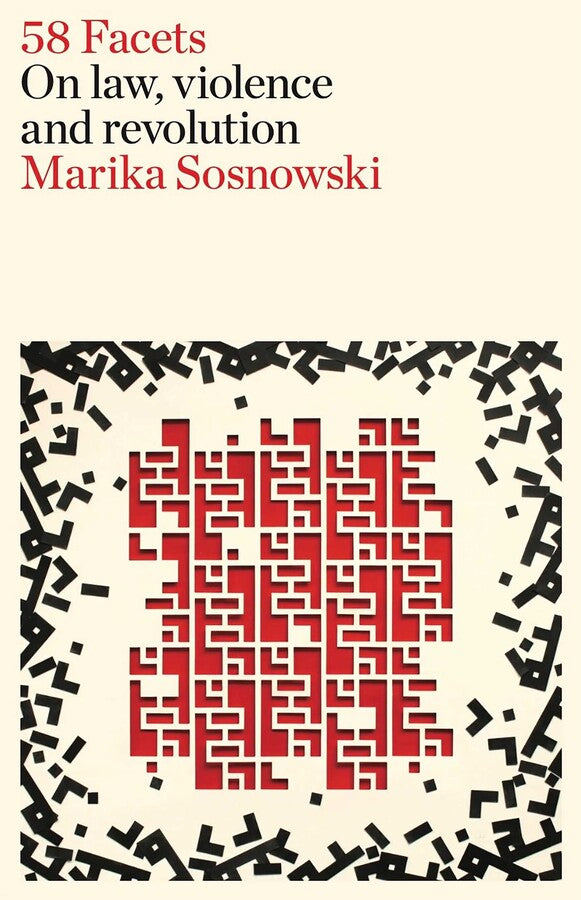

58 Facets: On law, violence and revolution

58 Facets: On law, violence and revolution

Couldn't load pickup availability

Part memoir, part exposé, 58 Facets weaves together the narratives of Holocaust survivors and Israeli war criminals with Syrian activists, revolutionaries and dissenters. It challenges us to go beyond the links we see in our lives to our felt experiences of the law, violence and revolution, and how these experiences travel across bodies, space and time.

Sam's Review

For most of us, the law is something we generally brush past, barely aware of its existence, following its rules with little questioning and challenged by its enforcers on the rarest of occasions. We see it as a protector, upholding the peace. Marika Sosnowski's latest book, 58 Facets: On law, violence and revolution, asks us to reconsider; to see the violence inherent to law and to witness how this violence can turn the rule of law into the rule of authoritarianism.

Sosnowski is well placed to make this argument. She's an Australian-qualified lawyer, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Melbourne Law School and a Research Associate at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) in Hamburg. She is also the granddaughter of both survivors and victims of the Holocaust, and 58 Facets weaves both their stories and the stories of Syrian activists who Sosnowski has worked with. In this way, she places her questions and arguments in both historical and contemporary contexts.

By using personal stories to illustrate the impact of the law, Sosnowski gives context and empathy to her arguments. When she writes that "[w]ithout the threat and use of violence, the law would neither function nor be effective" it would be easy to write her off as the cliched lily-livered liberal. It is much harder to accuse her of this when she goes on to describe the experiences of Syrians from the town of Daraya, who were "surrounded and besieged...stabbed and shot at point-blank range" and bombed to the point where "when people hear barrel bombs falling, they pray for them to be explosives, not napalm". All because they dared to democratically elect a local council in opposition to the regime of Bashar Al-Assad.

The easy counter to such examples would be to say that Al-Assad was a despot, an outlier; that such acts couldn't happen here. In describing Australia's Terra Nullius, Sosnowski immediately disproves such arguments, showing that "[w]hite Australian Law was no stranger to gross acts of violence in the name of 'protection'". Her observation that the current camps, known as immigration detention centres, on Christmas Island, the Cocos Islands and Ashmore Reef, were named 'The Pacific Solution' demonstrate that we are not only "tone-deaf to history" but still not as immune from or to violence as we might think.

Camps and checkpoints appear throughout 58 Facets. The death camps of the Third Reich or the refugee camps of war zones may be the ones that first spring to mind, but as Sosnowski notes, "camps are everywhere if you look for them" - camps for First Nations people, the aforementioned immigration detention centres, the "the only slightly more innocuous Chinatowns, the Japtowns, the Koreatowns" and "large open-air camps like Gaza that we are constantly told are not actually camps". They exist within a nation but often outside its laws: the exception to the rule of law. Checkpoints, meanwhile, whether the permanent type at national borders or the impromptu roadside variety, are "a prime site for the arbitrary interpretation of the law and the (legitimate or illegitimate) use of violence" because they are "made up of an unsteady collection of practices, relations and feelings." Both become literal and metaphorical points of confrontation, where our individual freedoms meet their limits; points where "[o]ne has to know how to read the landscape, how to run, bend, twist and move across a shifting jungle of laws" or face losing one's freedom.

Solosnowski writes of camps with the inherited knowledge of those whose grandparents and parents survived them. Her grandparents escaped the Nazi camps in Europe but ended up in the Japanese camps in Indonesia, before finally arriving in Melbourne. Their experiences, those of the family members who also survived and those that didn't, provide the most personal questions of the book: what trauma and knowledge do we carry from our parents and grandparents, and what do we owe to their legacy? In 1940, shortly after the Nazis instituted ID cards in the Netherlands, Soswnowski's great-grandparets escaped through France to the safety of Spain, their ID cards enabling them to 'legally' emigrate. But they lived knowing that these same ID cards were used to identify, capture and kill tens of thousands of Jews who didn't get out in time. Sosnowski's great-uncle Charles escaped along the same route. He went on to join the British Army, becoming an investigator of Japanese war crimes, before joining the Israeli army and becoming Lieutentant Colonel Military Commander of the Gaza Strip. He instituted the same ID card system that almost killed him to identify every Palestinian. Sixty-seven years later, watching the actions of the Israel Defence Force, Sosnowski is "a tangle of emotions; I am contemplating my own complicity. I am in the isthmus, the line that separates the sun and its shadow."

In witnessing the bravery of her grandparents and the Syrian activists, Solosnowski comes to the conclusion that revolution is required when law steps into authoritarianism. The subtlety of her argument is that revolution doesn't only require the heroic sacrifice of those killed standing in front of tanks but the ongoing, everyday acts which are carried out in the face of fear and oppression; acts "as simple as a joke that undermines how you think things ought to be." Whether jokes shared in whispers between friends, or passports printed in hiding by opposition parties helping citizens escape war zones, Solosnowski shows that revolution comes in many forms and over many timelines. Quoting Palestinian poet and performance artist Fargo Tbakhi, Solosnowski tells us that "[w]e never know whether we are closer to the end of a revolution or the beginning, whether we are nearer liberation than defeat". Like the 58 facets of a diamond from which the book takes its title, revolutions are formed slowly, continuously and inextricably. And books like 58 Facets quietly inspire them.

When you have been forcibly displaced from your home, the revolutionary dream of what should have happened … stays alive as a utopian beacon of happiness that will (possibly) never come to pass. To be content and make a meaningful life from the ruins of that wrenching and uprooting is a small, everyday miracle that others easily overlook.

58 Facets is like a beautifully cut jewel, the kind Marika Sosnowski’s grandfather would have bought, cut and sold after he arrived in Melbourne in 1947, having passed through a checkpoint minutes ahead of Nazi occupiers, via a Japanese internment camp in Java and a migrant accommodation camp just outside of Brisbane. If you hold it up to the light you will catch different stories in each of its many facets. You will have the table, the bezel, the star and the upper girdle, the lower girdle, the pavilion and the culet. You will have the dreams, the checkpoints, the documents, the bribes, the camps, the occupation and the resistance.

Part memoir, part exposé, 58 Facets weaves together the narratives of Holocaust survivors and Israeli war criminals with Syrian activists, revolutionaries and dissenters. It challenges us to go beyond the links we see in our lives to our felt experiences of the law, violence and revolution, and how these experiences travel across bodies, space and time.

Share