Maria Reva

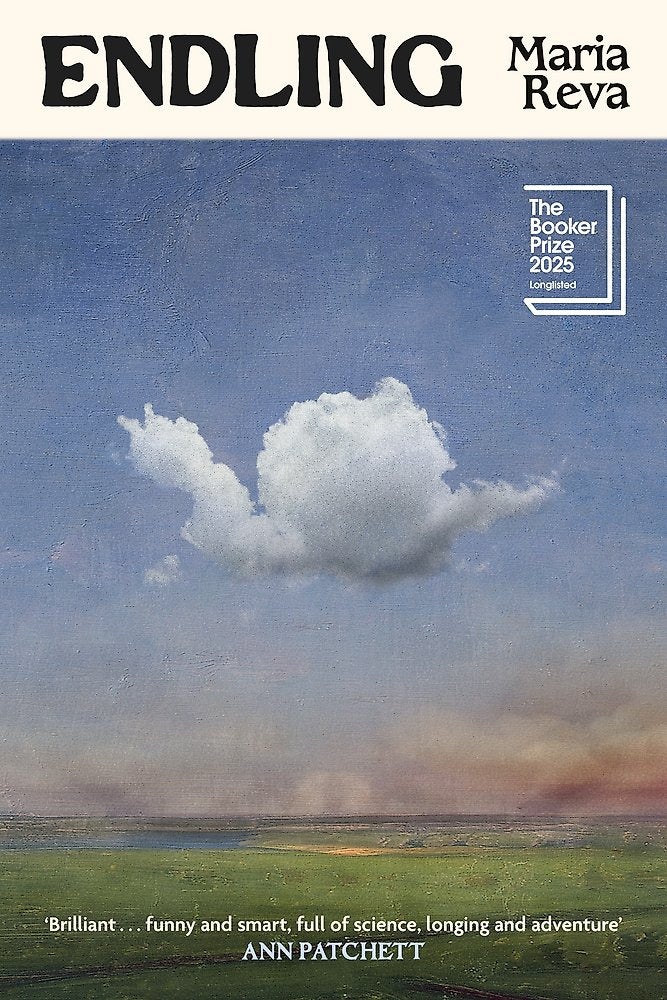

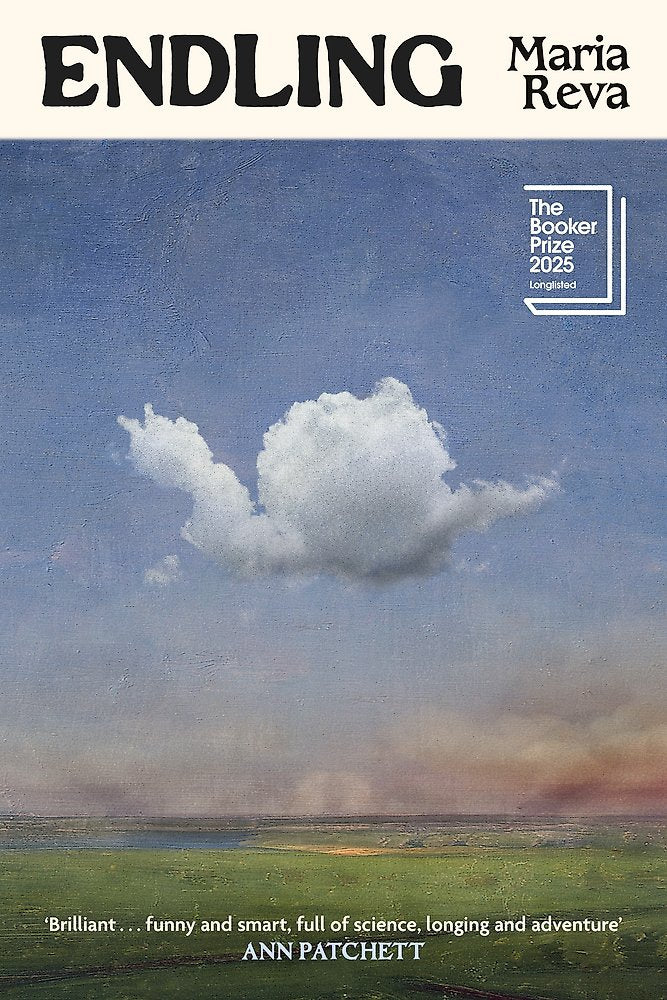

Endling

Endling

Couldn't load pickup availability

An unforgettable debut novel about the journey of three women and one extremely endangered snail through contemporary Ukraine

Sam's Review

The writing of a book can be interrupted by many things: illness, family matters, a loss of ideas, even war. Maria Reva’s Booker longlisted novel Endling addresses the impact of the latter factor head-on, with wit, great imagination and a breaking of the fourth wall. And snails; rare, last-of-their-species, snails.

Reva is a Ukrainian-born Canadian. Her previous book, a short story collection called Good Citizens Need Not Fear, is set in an apartment block in the country of her birth. Inspired by Reva’s family’s history, the collection intertwines the lives of residents of the block in the period leading up to and immediately following the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989. Her latest book, Endling, recently long-listed for the Booker Prize, is also set in Ukraine, and also references her family’s history. It’s placed around another seismic event: the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The narrative begins prior to the war, with the near-futile attempts of a scientist called Yeva to locate, rescue and breed rare snails before they become endlings - the last of their species. While Yeva is desperate for her snails to breed, she has no interest in sex herself. Her mother despairs about her daughter, “whose beautiful eggs promised beautiful children but were shrivelling with each passing day.” While Yeva gives neither babies nor love much thought, remaining focused on her work, she nevertheless recognises and uses the power of her good looks to earn the money her scientific endeavours do not. She accepts a paid invitation to attend romance tours at which western men come to meet and marry Ukrainian women who, as the marriage agency advertises, have “slant eyes and thin waists like Genghis Khan. Mysticism and fine fashion from the Tatars. Pragmatism and hair plaits from the Poles. Flammable spirit from the Balkans, et cetera.”

At the romance tour, Yeva meets sisters Nastia and Solomiya, who pose as a hopeful bride and her translator, respectively. But neither is looking for a husband: they are the daughters of feminist activist and puncher of Putin, Iolanta Cherno, who has been missing for over a year. Nastia hatches a plot to kidnap eleven of the hopeful bachelors as a protest against the marriage industry; and desperate to contact her mother, she co-opts Yeva and her mobile laboratory/van into her plan. The final person in the unfolding Coen Brothers-esque farce is Pasha, a twelfth bachelor, who joins the eleven men on what they believe is a special event, only to find himself locked in Yeva’s van. Like Reva, Pasha is a Canadian born in Ukraine; and with his conflicting feelings of alienation and homesickness for the place of his birth, is arguably a stand-in for the author.

At this point in a quick-witted, politically charged and somewhat absurd story, I’d been expecting a manhunt for the women and their kidnapped bachelors followed by a final showdown, delivered with gusto and imaginative flair. But Part II of the novel moves into metatextual terrain: Reva the author interjects, telling us a story about her writing of this book and how the Russian invasion upended her world, rendering meaningless any of her ideas. This is particularly evident when her phone becomes filled with images of bombed houses that look like they belonged to her grandparents, aunties and uncles. She writes of her ethical dilemma thus: “I was writing about a so-called invasion of Western bachelors to Ukraine, and then an actual invasion happened. Even in peacetime, I felt queasy leaning into not one but two Ukrainian tropes, ‘mail-order’ brides and topless protestors. To continue now seems unforgivable.”

There follows a surrealist conversation between an author and a yurt-maker about the stitching together of different novels; letters between Reva and the editors of newspapers requesting that Reva’s essays dial down the humour and focus on “watching the horror unfold from abroad (gentle emphasis on horror)”; and a grant application to the Commonwealth Arts Foundation. What follows appears to be a conclusion to the novel – a brief chapter about Yeva, Nastia, Sol and the bachelors, with the notes that typically come at the end of a book. Is that it, then? Was the story abandoned, finished but not really, put into a drawer as a relic of a time before the war?

No. The yurt maker reappears, along with the story: Yeva, Nastia and Sol plan their next steps, a seemingly doomed journey to Kherson, the heart of battle, in search of a snail that could be a twig on a tree in the background of a photo, posted to Instagram, showing the outbreak of war. The bachelors are still in the truck, strangely submissive (the only misstep I found in the book). The marriage agency is on the phone demanding the women return the men. Pasha is dreaming of finding his Ukrainian bride and his Ukrainian home. Nastia is calculating whether war will make her mother more likely to see her protest. Yeva is hellbent on finding her almost mythical endling. And Sol is just trying to keep things together.

The novel asks us confronting questions. In the face of war and the invasion of your country, what would you do? In the midst of an existential crisis, could you retain rationality? Would you flee, fight or carry on as normal? The absurdity of Endling asks us to consider these unanswerable questions, along with the sense of uselessness felt by those watching the war unfold from afar when those closest to them are stuck in the middle. None of us knows how we would react to the horrors of war. And while creating art might feel shamefully inadequate when you could be firing a gun or carrying a stretcher, Reva has done what the best art should do: hold up a mirror and ask its creator and its beholder to consider their metaphoric reflections. What do we value, and why? And what would we sacrifice to keep it?

Publisher Review

'A fierce and funny road-trip novel ' GUARDIAN, the 50 hottest books to read right now

'A thrilling ride' FINANCIAL TIMES

'Brilliant and heart-stopping' LOS ANGELES TIMES

'Startling and ambitious' NEW YORK TIMES

'Animated by dark humor and cool fury' NEW YORKER

'Virtuosic' NPR

'Dexterous and formally inventive' MARCEL THEROUX, GUARDIAN BOOK OF THE DAY

'Remarkable' WASHINGTON POST

Ukraine, 2022. Yeva is a maverick scientist who scours the country's forests and valleys, trying and failing to breed rare snails while her relatives urge her to settle down and start a family of her own. What they don't know: Yeva already dates plenty of men-not for love, but to fund her work - entertaining Westerners who come to Ukraine on guided romance tours believing they'll find docile brides untainted by feminism.

Nastia and her sister, Solomiya, are also entangled in the booming marriage industry, posing as a hopeful bride and her translator while secretly searching for their missing mother, who vanished after years of fierce activism against the romance tours.

So begins a journey of a lifetime across a country on the brink of war: three angry women, a truckful of kidnapped bachelors, and Lefty, a last-of-his-kind snail with one final shot at perpetuating his species.

Share