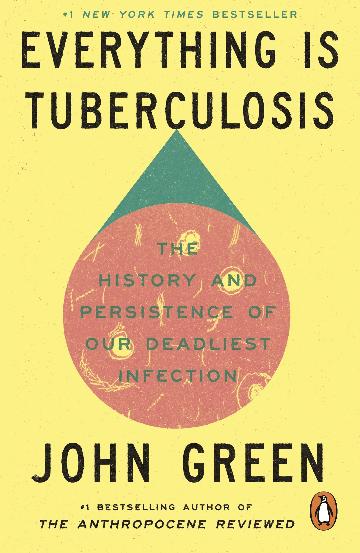

John Green

Everything Is Tuberculosis

Everything Is Tuberculosis

Couldn't load pickup availability

Out in Paperback 17 Mar 2026 @ $26.99

Hard back version available now for $36.99 - call the Lane 08-9384-4423 to order your copy or email us at mailto:orders@lanebook.com.au

“Green’s new book revels in the kind of moral clarity that shows how making the sick “more than human” is the same trick as making them “less than human”.”

John Green’s Everything Is Tuberculosis: The History and Persistence of Our Deadliest Infection isn’t simply a history of a pathogen; it’s an anatomy of the stories humans build when the facts are unbearable. He pauses on our compulsion to ask why suffering happens and to settle—too quickly—on an explanation that feels comprehensible. He points to the danger Susan Sontag named: the moment we give disease a meaning, we begin punishing the sick with our metaphors. Green’s book is structured as a braid—Henry’s contemporary story (a young TB patient Green met in Sierra Leone) threaded through the scientific and social history of tuberculosis. The argument tightens like a noose: TB persists less because of bacterial cunning than because of human choices, incentives and inequities that decide whose breath is worth purchasing.

One of the book’s key insights is that romanticising illness is not kindness; it is a distancing technique. When tuberculosis became too widespread to be dismissed as mere moral failure, nineteenth-century Europe and the United States—unable to tolerate the “robber of youth”—began to romanticise consumption as beautiful and ennobling, a sign of sensitivity and brilliance. Green refuses the comfort of that idea. He shows how romance and stigma are cousins, not enemies: to elevate the consumptive into a creature of special genius is still to make them “other,” safely separate from the healthy majority. He traces the way TB’s “look” was absorbed into aesthetic life—pallor, thinness, fever-glow—until “consumptive chic” became a real cultural phenomenon. It was reinforced by beauty standards and by literature that could not resist turning breath into spirit. In the United States, Green notes that when TB rates declined there was real concern this might “harm the quality of American literature.” Gothic Romanticism did not merely borrow tuberculosis as a plot device. It breathed an air in which illness was interpreted as depth, refinement, even destiny—right down to Charlotte Brontë’s comment, written as her sister was dying, that “Consumption… is a flattering malady.”

Green’s genius is that he makes you see the afterlife of that aesthetic without letting you hide inside it. Growing up in Perth, I remember Gothic nightclubs like The Loft and The Firm—rooms full of arts graduates in black, faces whitened, performing a kind of modern consumptive chic as if the Brontës had been reborn with student cards and eyeliner: pallor as seriousness, thinness as a credential, suffering as style. Green’s history makes that echo legible: the consumptive aesthetic didn’t vanish when the science arrived; it seeped into our cultural idea of seriousness and sensitivity, and it still flatters us with the lie that suffering is a credential. The achievement of Everything Is Tuberculosis is that it dismantles that lie without sneering at the art it helped produce. It allows us to keep the literature —Keats, the Brontës, the whole aching tradition — while insisting we stop using it as an excuse to tolerate preventable suffering in the present.

Share