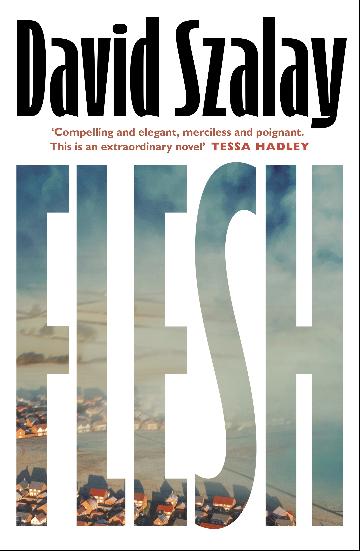

David Szalay

Flesh

Flesh

Couldn't load pickup availability

From Booker-shortlisted author David Szalay, comes a propulsive, hypnotic novel about a man who is unravelled by a series of events beyond his grasp.

SUSAN'S REVIEW

Among other awards and acclamations, Hungarian British writer David Szalay has twice been shortlisted for the Booker Prize: for his unsettling All that Man Is, published in 2018, and for his latest novel, Flesh. While the earlier work provides glimpses of nine different versions of masculinity, Flesh explores the life of one man, István, from adolescence to middle-age. But while this new novel is also a study of a particular kind of masculinity, it is also an expression of anomie: a profound sense of social alienation and isolation that might be said to describe the modern human condition, regardless of gender. Despite the momentary pleasure that István finds in the life of the flesh — sex, the feel of sun and water on the skin, consuming alcohol and drugs — he ultimately experiences his life as profoundly empty, without purpose or meaning.

Yes, Flesh is that kind of book. But what sets it apart in the contemporary zeitgeist of bleakness and despair is the subtlety of its craft and the complexities of what is not said. Flesh takes the form of a Bildungsroman — a coming-of-age novel; but instead of following the central character’s life in a series of cause-and-effect events, it works by presenting gaps, repressions and evasions. The very form of the novel, in which discrete chapters deal with different stages of István’s life, creates a portrait of a compartmentalised man, unable or unwilling to piece himself together. As well, he typically acts on impulse, seemingly indifferent to his motives or to outcomes. The opening chapter establishes this psychology, when, as the teenage son of an impoverished single mother living in a village in Hungary, he is seduced by a middle-aged woman for whom he feels little attraction, then pushes her angry husband down the stairs. When the police ask him if he intended to kill the man, the boy’s only and repeated answer is a seemingly genuine “I don’t know.” Nor is this the predictable response of a frightened or confused adolescent. For the rest of his adult life — a stint in the Hungarian army deployed to Iraq, working as a private bodyguard in London, marriage to a wealthy woman, followed by a downward spiral — István remains incurious about the workings of his inner life. He is a person adrift; without a place in which to belong or a coherent sense of self.

In each stage of his life, with one important exception, he is acted upon — by other people and by his immediate physical needs — rather than making considered choices. He is typically seduced by women rather than taking the initiative, and when asked if he found the sex enjoyable, merely describes it as “OK.” His work as a bodyguard is a symbol for his lack of agency; in a scene imbued with a faint sense of menace, his employer kits him out with expensive clothes, as if István is a dressmaker’s dummy. Even a spontaneous act of courage, like trying to save the life of a buddy in Iraq, doesn’t lift him from the fog of passivity; when his commander asks him why he’s leaving the army, István can only repeat “I don’t know, Sir.” And while the novel hints in several places that he’s been traumatised by the experience, he merely, and obligingly, follows the psychiatrist’s advice to take medication. He gets better sleep, then gives up the medication, as if he didn’t have a problem that needed a resolution; as if there wasn’t a problem at all.

The one exception to this narrative of passivity is István’s ambitious plans as a property developer. His marriage to a wealthy widow — a seductress who proposes to him — gives him a taste of the power that comes with having unlimited amounts of money. In this section of the novel, we seem to be reading a different genre, a high-stakes drama of competing wills. The generic anomaly seems to be precisely the point: István plans are thwarted by his outsider status as a working-class man, and by the external forces of political influence and the law. Without preaching to the reader, the novel reveals the essential powerlessness of ordinary people against the might of the capitalist system. The gender politics of Flesh, however, are difficult to pin down. Is István’s treatment of women as sexual objects intended to be seen critically? That his sexism, bordering at times on misogyny, is a symptom of his morally impoverished view of the world? It would take an essay to unpick the novel’s perspective, but for the moment, I remain ambivalent.

The novel’s vision of an ultimately futile life is enacted in a uniformly plain style that makes Ernest Hemingway sound like a lyric poet. The language is stripped ruthlessly bare; the tone is often enervated and flat. But against all the odds, this doesn’t make for dull reading. On the contrary, Flesh is a strangely compelling and even, at times, poignant read about a man for whom fleeting bodily contentment is more satisfying than the arduous process of introspection. David Szalay’s new novel won’t be to everyone’s taste — it’s sombre, and sometimes deliberately crass — but it does what the best novels always do: it asks important questions about the realities of power and gives reader the freedom to read between its carefully chosen lines. With echoes of seminal texts like Albert Camus’ novel The Outsider and T.S. Eliot’s poem The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, Flesh is also its own particular form of provocation and ambiguity.

Flesh is available in store now.

PUBLISHER REVIEW

From Booker-shortlisted author David Szalay, comes a propulsive, hypnotic novel about a man who is unravelled by a series of events beyond his grasp.

'A revelatory novel' - Sunday Times

'Brilliance on every page' - Samantha Harvey, author of Orbital

A propulsive, hypnotic novel about a man who is unravelled by a series of events beyond his grasp.

Fifteen-year-old Istvan lives with his mother in a quiet apartment complex in Hungary. New to the town and shy, he is unfamiliar with the social rituals at school and soon becomes isolated, with his neighbour - a married woman close to his mother's age - as his only companion. These encounters shift into a clandestine relationship that Istvan himself can barely understand, and his life soon spirals out of control.

As the years pass, he is carried gradually upwards on the twenty-first century's tides of money and power, moving from the army to the company of London's super-rich, with his own competing impulses for love, intimacy, status and wealth winning him unimaginable riches, until they threaten to undo him completely.

Spare and penetrating, Flesh is the finest novel yet by a master of realism, asking profound questions about what drives a life- what makes it worth living, and what breaks it.

Chosen as a 'Best Book of 2025' by the Guardian, Observer, Financial Times, Daily Telegraph and Daily Mail.

'Flesh is a wonderful novel - so brilliant and wise on chance, love, sex, money' - David Nicholls, author of One Day

'It's been a long time since I've been swallowed whole by a novel the way I was by this one ... So much searing insight into the way we live now' - Observer

'Compelling and elegant, merciless and poignant. David Szalay is an extraordinary writer' - Tessa Hadley

Share