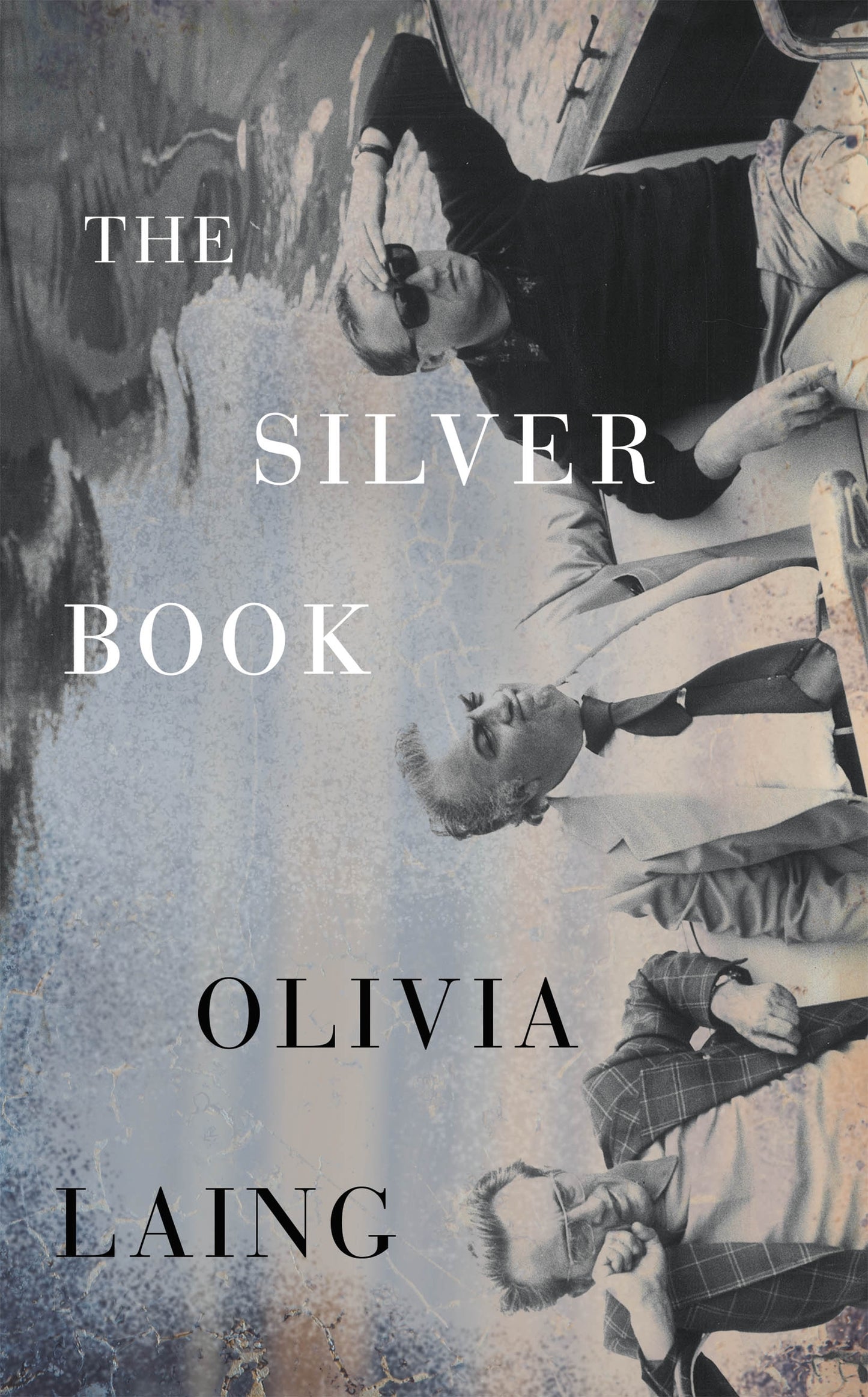

Olivia Laing

The Silver Book

The Silver Book

Couldn't load pickup availability

I’ve long been a fan of contemporary British writer Olivia Laing. Her work is intellectually provocative and stylistically elegant, as well as wide-ranging in its choice of subjects: everything from creativity, loneliness and the writing of biography to the AIDS crisis and gardening as a salve for anxiety and loss. Her second novel is typical Laing in its blending of fiction and history; her immediate subject is the politics of Italian cinema in the 1970s.

At the centre of the story is the making of Pier Pasolini’s notoriously horrifying movie Salò: The 120 Days of Sodom. Much has been written about what Laing has elsewhere called Pasolini’s “apocalyptic masterpiece”: an allegory of fascist Italy set during World War Two, which includes sickening images of teenage boys being physically and psychologically tortured, raped, mutilated and murdered. Much has also been written about its director: movie-star handsome; openly gay in a country that criminalised homosexuality; a towering figure in the history of cinema; a left-wing provocateur whose essays denounced the Italian government, the Catholic Church and the secret service as agents of totalitarianism.

Laing has chosen to represent this familiar material obliquely; to the side (she also mercifully spares us the gruesome details of Salò). As if she were a movie director herself, she has used what’s called a point-of-view shot or subjective camera: the novel’s “eye” is a naïve English teenager, a fictional character called Nicholas, who is taken as a lover by the historically actual Danilo Donati, arguably the most celebrated costume designer in the history of cinema. Employed as Donati’s assistant, the re-named Nico receives an ‘education’ in the cinematic art of illusionism: he learns about, for example, the painstaking transformation of actors through costume and make-up; the ingenious use of material to create snow and faux interiors; the casting of local Italian villagers to become highly choreographed sexualised bodies. Nico also learns about the tedium of endless takes and the endless scrabble for funding that makes “the dream factory” a reality. The details of production and direction was a source of fascination for me, as well as for Nico (chocolate biscuits made into turds is a particularly compelling example!)

What Nico fails to see, however, is the political context in which Salò was made: Italy’s fascist regime during World War Two and the resurgence in the country of fascist organisations in the 60s and 70s that led to an epidemic of assassinations and terrorist attacks (the so-called Years of Lead). Laing uses her editorial skills to occasionally ‘cut’ to the point of view of Donati, who has witnessed at first hand the past horrors of fascist Italy.

At one point he recalls “[p]eople starving in their rooms … Denunciations, roundups, missing people, deportations. The trucks, the trains” – which are said to “animate every stitch” he makes in his work as a costume designer. A similar and deeply moving ‘cut’ is an extended scene in which Pasolini tells Nico about the death of his younger brother Guido as a resistance fighter in the war. Up until this point, Pasolini has been seen only from the outside; through Nico’s eyes, he is a body in constant motion or sitting silently alone. But this poignant scene reveals the anger behind the making of Salò: a call for justice and retribution which Pasolini understands is both deeply personal and ethically necessary, and a deeply felt warning about future violence and suppression of freedom. The effect of such brief ‘cuts’ to political history not only reinforces the naivete of Nicholas’ attraction to the surface glamour of cinema. It also represents fascism as a sinister subterranean force; one which in real life might have caused the grotesque and as yet unsolved murder of Pasolini at the age of 53, three weeks after the completion of Salò.

The novel’s political dimension is also evident in its depiction of sex. Through Nico’s eyes, the sexual activities of the film crew are presumed to be immune from or untouched by public judgement: boys hustle, men cruise, people casually swap partners. While there is jealousy and betrayal, Nico’s overall impression is of a self-enclosed hedonistic culture. Later in the narrative, however, he laments to his lover Donati: “1975 and a man has landed on the moon, but I can’t even kiss you in public.” This intrusion of political reality into the so-called private realm of human relationships is a potent reminder of the power of the Catholic Church to not only criminalise homosexual behaviour but also to prohibit gestures of emotional intimacy between men. Laing’s technique here, as throughout the novel, is to immerse us in the magic world of filmmaking, and then to abruptly remind us that every space, including those of sexual relationships and art, is political: a continuing contest between the powerful and the powerless; between those with a voice and those who are silenced.

As a fundamentally political narrative, The Silver Book is thoughtfully oblique and skilfully restrained. The novel will enhance Olivia Laing’s reputation as an important chronicler of cultural crises and malaise. It might even encourage you to watch Salò, a movie that director Michael Haneke, not averse to depicting rape, incest and sexual violence on screen, made him so scared that he was “sick for 14 days”:

To this day, I haven’t drummed up the courage to watch it again. Never again did I look into such a deep abyss and rarely have I learned so much.

(I think I will pass on this one.)

Share