1

/

of

1

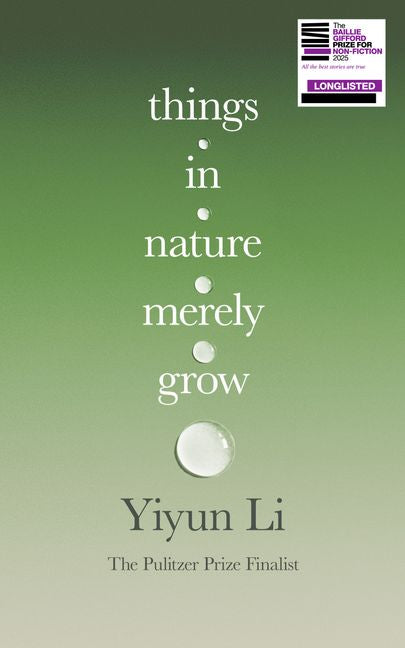

Yiyun Li

Things In Nature Merely Grow

Things In Nature Merely Grow

Regular price

$32.99 AUD

Regular price

Sale price

$32.99 AUD

Taxes included.

Shipping calculated at checkout.

Quantity

Couldn't load pickup availability

LONGLISTED FOR THE BAILLIE GIFFORD PRIZE FOR NON-FICTION 2025.

A remarkable, defiant work of radical acceptance from acclaimed Pulitzer Prize finalist Yiyun Li as she considers the loss of her son James.

SUSAN'S REVIEW

Chinese-born writer Yiyun Li moved to America in 1996 to undertake a PhD in immunology, but after enrolling at the prestigious Iowa Writing Workshop, partly to stave off boredom, she fell in love with the wondrous possibilities of language and story (she also completed her PhD). She has described her decision to become a writer as a deliberate act of revenge against a mother who repeatedly beat and humiliated her, and who insisted that her daughter pursue a career in science. In response to that brutal denial of her-self, Li later made a conscious choice to respect her own children’s desire to be the person they wished to be. Her older son Vincent — flamboyantly androgynous and emotionally expressive — chose in his seventh grade to wear a pink dress to school, unafraid of being bullied. Five-year-old James — intellectually precocious and almost entirely non-verbal — showed his mother a sign he’d made in response to adults repeatedly asking him why he didn’t speak: IM NOt TALKINhg Becuase I DON’t WaNT TO! He was in kindergarten at the time. Li and her husband neither judged their children, nor tried to make them “normal.” She writes in her new memoir, Things in Nature Merely Grow, that it was ethically and psychologically crucial to accept their sons’ choices in life.

But. Early in the same book, Li tells us: “There is no good way to state these facts … My husband and I had two children and lost them both: Vincent in 2017, at sixteen, James in 2024, at nineteen. Both chose suicide, and both died not far from home.”

Yiyun Li has written two memoirs to honour her sons’ different ways of being in the world. Where Reason Ends, published in 2019, is a tribute to Vincent in the form of an imagined dialogue — passionate, sometimes playful, sometimes combative — between him and his mother. By contrast, Things in Nature Merely Grow, a tribute to the prodigiously intelligent James, is primarily a rational argument about those famous words: “To be or not to be; that is the question.” Both deeply personal and abstractly philosophical, the book offers insights into James’s possible motives for committing suicide. Li wonders whether her own history of chronic depression and two suicide attempts influenced James’ choice to end his life. She strives to understand the habitually silent young man when he describes the turmoil of his inner life. Above all, Li believes that Vincent’s suicide might have been a major factor. The brothers were extremely close; Vincent was the one person to whom James spoke freely and at length. But after such speculation, as well as self-doubt and guilt, Li feels no closer to understanding what she calls his beloved “essence.” In the light of such impenetrable complexities, and as a means of trying to endure her loss, Li ultimately chose to adopt what she calls the position of radical acceptance.

The concept of radical acceptance is indeed the very fabric of the memoir. Rejecting the notion of “grieving” because to her it implies the possibility of healing, Li argues that radical acceptance is a way to inhabit what she calls “the abyss” of profound loss without trying to escape it. It is at the same time a mark of respect for her sons’ choices, as well as a refusal of the platitudes of ‘self-help’ pop psychology. Li writes that she is acutely aware that other people would judge the concept of radical acceptance as cold, as even heartless; “evidence” that she didn’t love her children. And judge people certainly did, in face-to-face encounters and by sending hate mail. But throughout such ordeals, or when dealing with people’s thoughtless or callous remarks about James’s death, Li tried to remain calm and composed. Nor is she outraged, as many people surely would be, when strangers offer condolences before asking her to read their manuscript or help them find a publisher. When the Chinese authorities denounce her as a cruel and evil mother, Li simply confirms, without bluster or self-righteousness, her earlier decision not to write in or be translated into her native tongue. And while there are moments in the book when Li writes of her sadness — treasuring her children’s left-behind objects, for example, or weeping uncontrollably when watching a performance of King Lear — they are all the more powerful for their infrequency, and for the straightforward manner of her narration.

Li also takes a reasoned approach to the problem of finding a language with which to express her response to James’s shockingly unexpected death. While she laments what she calls “a flabbiness or a staleness (of language) after a catastrophe,” she continues that “if one has to live with the extremity of losing two children, an imperfect and ineffective language is but a minor misfortune.” Li is not a precious writer whose pronouncements of verbal inadequacy are designed to display their integrity; rather, she offers the voice of wisdom as a mother about what ultimately matters in life. Her choice of words to present a reasoned argument is also a mark of respect and admiration for a son who, at the age of three was reading encyclopedias and in his final year of high school did little else but read the works of philosopher Wittgenstein: a thinker and a writer who even sophisticated students of the discipline find baffling, if not incomprehensible. However. while Li privileges reason as her way of dealing with James' death, her book is not without powerful moments of emotion: gazing at the flowers James loved; the poignancy of touching the objects her left behind; gratitude for the kindness of friends.

I first encountered Yiyun Li’s writing when I read her 2009 debut novel The Vagrants, a chilling account of poverty, hunger and fear under Communist rule, set in a Chinese village. A year later, I heard her speak about her novel at the Sydney Writers Festival: I can still recall her quiet, steady voice and her gentle smile, her hands folded neatly in her lap. She couldn’t have known, of course, that her later writing — short stories, memoirs and novels — would be awarded prestigious prizes, or that she would be appointed a professor of creative writing at Princeton University. Nor could she, a childless young woman embarking on a career as a writer, possibly know that she would become the mother of two sons who chose to commit suicide.

In confronting, both personally and philosophically, the daunting question of “to be or not to be,” Li has written a courageously unconventional book that encouraged me to re-think traditional ideas about parenting, friendship and love. It asks me to suspend easy moral judgements. It reminded me, as the best writers do, that there are no solutions to life’s insoluble experiences. I will read the book again to reflect on its complex layers of meaning.

Things in Nature Merely Grow is available to order at the Lane Bookshop.

Susan

PUBLISHER REVIEW

LONGLISTED FOR THE BAILLIE GIFFORD PRIZE FOR NON-FICTION 2025

'Unforgettable' SUNDAY TIMES

'Courageous' OBSERVER

'One of the most important books to be published in years' SARA COLLINS

'There are few writers with Li’s power' DOUGLAS STUART

The best book I have read this year’ DAVID NICHOLLS

'I will return to it for the rest of my life' CHARLOTTE WOOD

A remarkable, defiant work of radical acceptance from acclaimed Pulitzer Prize finalist Yiyun Li as she considers the loss of her son James.

'There is no good way to say this,' Yiyun Li writes at the beginning of this book.

'There is no good way to state these facts, which must be acknowledged. My husband and I had two children and lost them both: Vincent in 2017, at sixteen, James in 2024, at nineteen. Both chose suicide, and both died not far from home.'

There is no good way to say this – because words fall short. It takes only an instant for death to become fact, 'a single point in a timeline'. Living now on this single point, Li turns to thinking and reasoning and searching for words that might hold a place for James. Li does what she can: including not just writing but gardening, reading Camus and Wittgenstein, learning the piano, and living thinkingly alongside death.

This is a book for James, but it is not a book about grieving. As Li writes, 'The verb that does not die is to be. Vincent was and is and will always be Vincent. James was and is and will always be James. We were and are and will always be their parents. There is no now and then, now and later, only, now and now and now and now.' Things in Nature Merely Grow is a testament to Li’s indomitable spirit.

As seen in the New Yorker, Vanity Fair, LA Times, TIME, and the Paris Review.

'To state that this courageous book is a testament to love is an understatement. One is left altered by it' OBSERVER

'A story of loss that is unlike any other book I've read … an unforgettable monument to endurance' SUNDAY TIMES

'Resolutely unsentimental, and yet it might wind you with its emotional force' GUARDIAN

'A memoir unlike others, strange and profound and fiercely determined not to look away' NEW YORK TIMES

'An extraordinary book’ SARAH MOSS

'A manifesto of living, not dying, and of how we endure the most unimaginable things' SINÉAD GLEESON, in THE WEEK

'A profound look at how a parent continues to live in a world without her children’ TIME

‘A book unlike any I've read, that brims with rare clarity and intelligence, with love and care. It will stay with me for a long time’ CECILE PIN

Share