John Connell

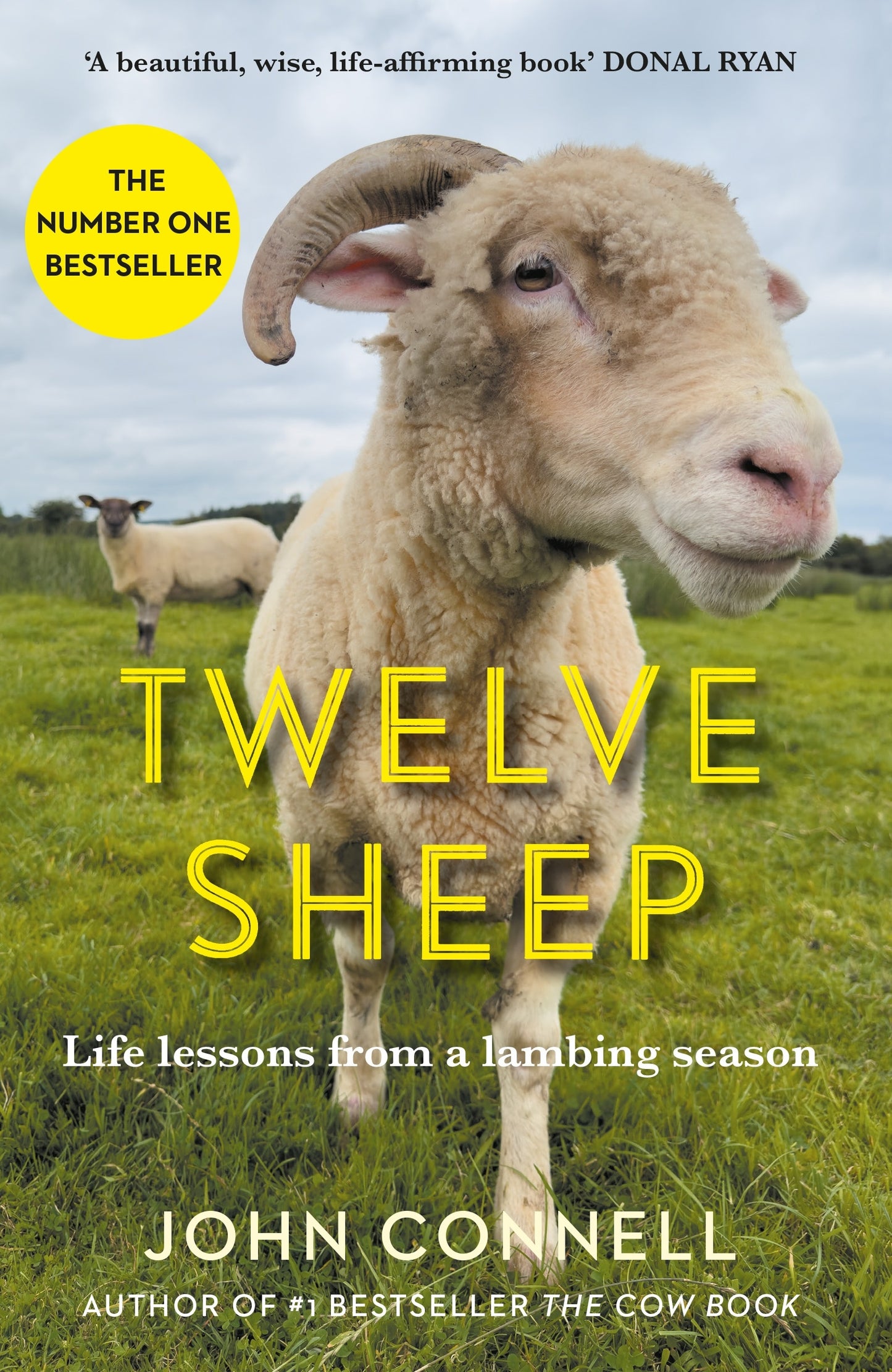

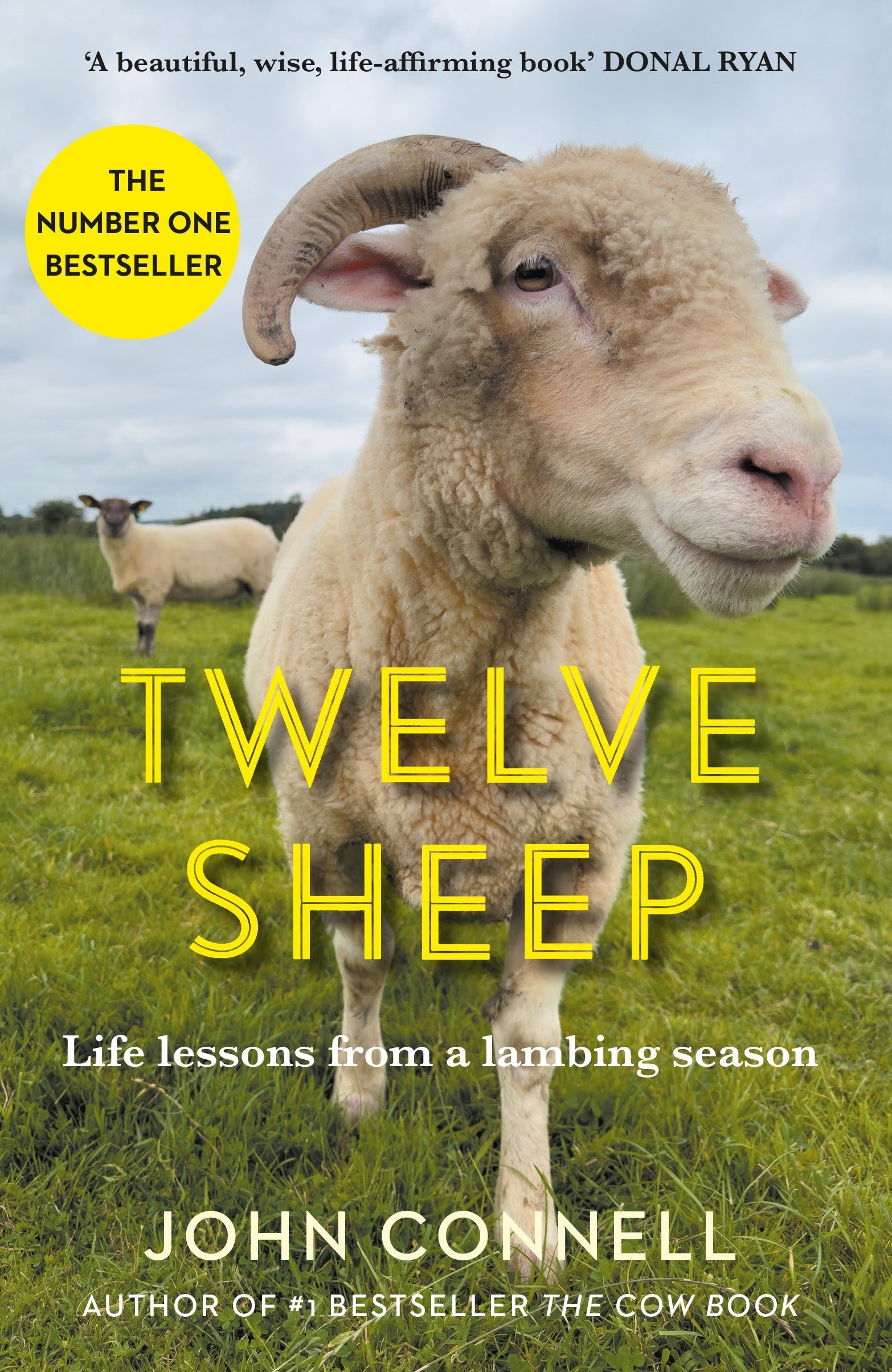

Twelve Sheep

Twelve Sheep

Couldn't load pickup availability

Peta’s Review

After listening to Phillip Adams’ thoroughly absorbing interview with Irish author and farmer John Connell, I knew that Twelve Sheep was a must-read for me. In the interview, Connell explained that after the success of his first publication, The Cow Book (2018), he suffered burnout, or what he describes as “soul-tiredness”. Knowing that he needed to heal, he decided to walk the Camino. Lore has it that you go on the Camino Walk with a question, you will find the answer, and this is what happened to Connell: towards the end of the walk, he came upon a shepherd and his flock, and he saw this as a sign to return to his family’s farm in county Longford, Ireland. He recalled Henry Thoreau’s belief in the “influence of the earth” to heal soul-weariness. Once home, he adopted 12 sheep — his “girls,” as he refers to them — nursing them through pregnancy and birth, then releasing their young lambs from the shelter of the lambing shed. The lessons the sheep taught him, and what they might teach us, Connell sees as fundamental: they challenge us to live in the present.

Sheep are ancient beasts. In ancient Turkey sheep were worshipped as gods. They gave meat, milk and wool and asked for little in return. And of course, the shepherd’s crook is a religious symbol. Connell believes Ireland has an historically strong connection with the land and her animals. They are integral to Irish mythology: the legend of Queen Maeve and the brown bull of Cooley, of the Celtic hero Cuchulain, of the god Dagda, god of fertility, of St Brigid the patroness of livestock and poets, just to name a few. Connell’s family also has a strong connection to the land, farming the land in Longford county since the 1700s.

Why twelve sheep, you might ask? Well, Connell quips, there are 12 months in a year, there were 12 disciples, and there are 12 Zodiac signs. Plus, he says, it doesn’t seem like a greedy number. Each of the twelve chapters outlines a lesson. In each chapter Connell draws on poets, philosophers and artists, such as Pliny the Elder, John Clare, Paul Coelho, Seamus Heaney, Bruce Pascoe, Carlo Rovelli and David Malouf, all of whom have a deep connection with nature and the land. For me the most powerful reference is to the painting Anguish (1878), by August Friedrich Schenck. The painting had a profound effect on Connell when he first viewed it. I had the same response. Do look it up: it is such a powerful image.

And what did the sheep teach Connell? He believes they have made him wiser. His “soul-tiredness” has been replaced by a physical tiredness, which Connell calls “a pleasing tiredness”. He feels rooted again in the land. His sheep have taught him “grace”. And me? As I read each lesson, I too considered my “soul-tiredness,” and what I could do to find some of the grace that Connell found with his sheep. A worthwhile addition to your bedside table reads, or a perfect gift for someone special.

Publisher’s Review

For John Connell, the lambing season on his County Longford farm begins in the autumn. In the sheep shed, he surveys the dozen females in his care and contemplates the work ahead as the season slowly turns to winter, then spring.

The twelve sheep have come into his life at just the right moment. After years of hard work, John felt a deep tiredness creeping up on him, a sadness that he couldn't shrug off. Having always sought spiritual guidance, he comes to realise that, in addition to the soothing words of literature and philosophy, perhaps the way ahead involves this simple flock of sheep. In the hard work of livestock rearing, in the long nights in the shed helping the sheep to lamb, he can reflect on what life truly means. Like the flock that he shepherds, this book is both simple and profound, a meditation on the rituals of farming life and a primer on the lessons that nature can teach us. As spring returns and the sheep and their lambs are released into the fields, skipping with joy, John recalls the words of Henry David Thoreau, reminding us to 'live in each season as it passes.'

Share