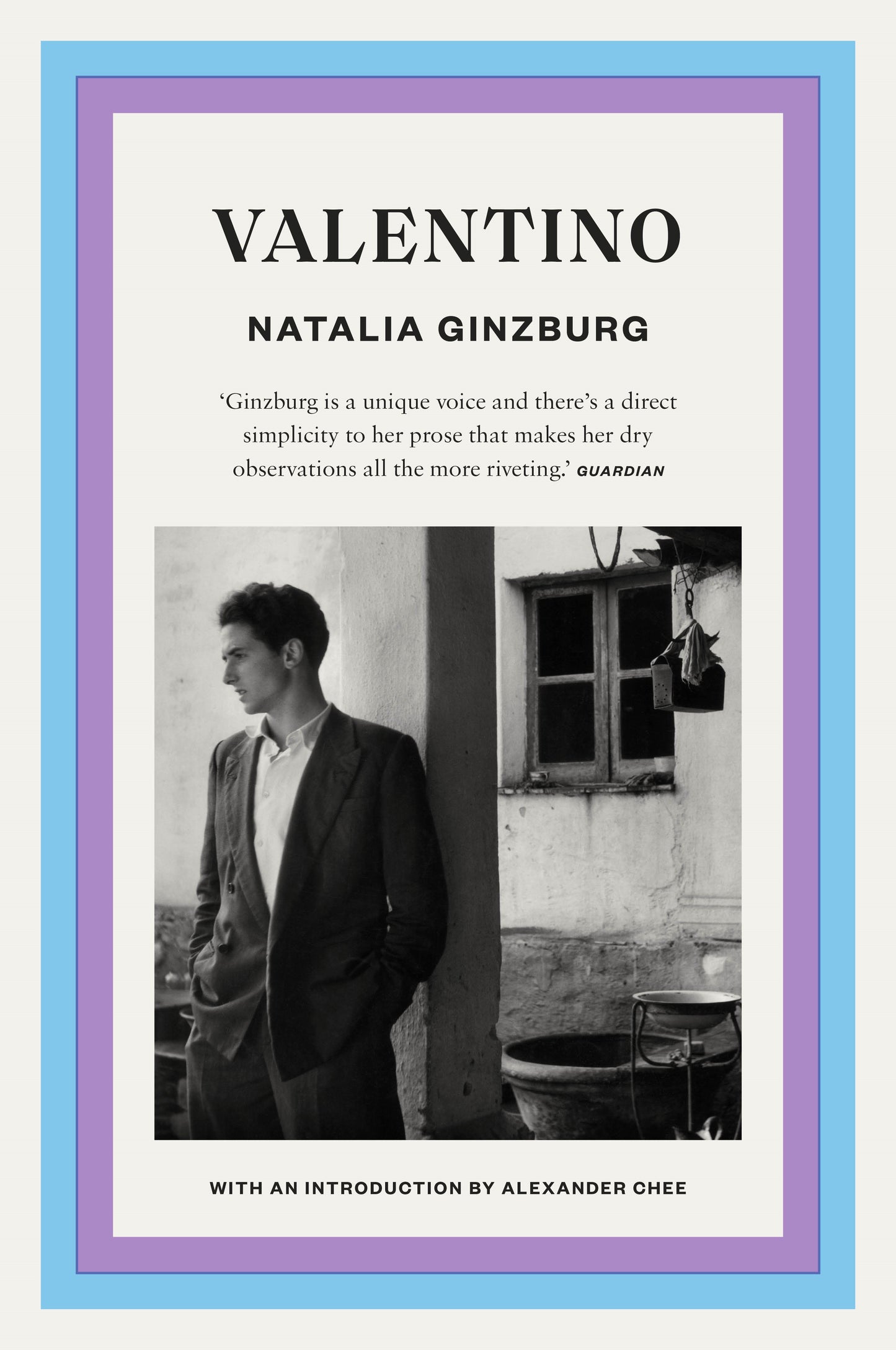

Natalia Ginzburg

Valentino

Valentino

Couldn't load pickup availability

Susan's Review

Italian writer Natalia Ginzburg’s novella Valentino, first published in 1957, uses the same deceptively simple prose as that of much-loved Irish writer Claire Keegan. Part of the pleasure and the challenge of their fiction comes from reading between the lines; being alert to the hints and implications beneath the ordinary surface of domesticity. Ginzburg’s narrator, Caterina, tells the story of her unhappy parents, her discontented married sister, and her handsome, vain, feckless brother Valentino, adored by a host of pretty and hopeful young girls. When Valentino marries the much older, wealthy and conspicuously ugly Maddalena, his parents and sister react with anger and disgust. By contrast, Caterina withholds her judgement, even in the face of what she fails to see is her brother’s increasingly selfish behaviour. As a result, this kind-hearted but naïve young woman remains oblivious to Valentino’s secrets and silence, as well as to the hidden lives of his wife and best friend.

Ginzburg, who died in 1991 after a lifetime of writing elegant fiction and political essays, remains widely admired by European and American readers. Like her other works of fiction, Valentino is distinguished by its subtlety — the critic Phillip Lopate describes Ginzburg’s style as ‘at once clear and shaded, artless and sly’ — as well as its insights into human motivation and the contaminating lure of money. This brief novella can be read in a single setting: it’s emotionally fraught, unexpected, and imbued with the pathos of unfulfilled lives. All this, as well as its ambiguous conclusion, will make for spirited discussion.

Whether you’re encountering Ginzburg’s work for the first time, or are already a fan, please treat yourself to Valentino, and to some of her other eight works of fiction.

Publishers Reviews

'So there is no one to whom I can speak the words thatmost need to be spoken, about the events which mostclosely concern our family and what has happened tous; I have to keep them bottled up inside me and thereare times when they threaten to choke me.'

Valentino is the spoiled child of doting parents who have no doubt he will be 'a man of consequence'.

His sisters, however, see him for what he really is: a lazy, indifferent and self-absorbed medical student who whiles away time with nights out on the town, resulting in a string of failed and incomplete classes. His parents' dreams are soon undone when, out of the blue, Valentino brings home Maddalena, a wealthy and strikingly ugly wife.

What ensues is yet another work of quiet devastation told with Ginzburg's unflinching moral realism and keen psychological insight, as the family is scandalised by Valentino's decision and suspicious of Maddalena's motives.

Share